Α2Γ ΑΡΧΙΤΕΚΤΟΝΕΣ

Πώς ξεκίνησε το γραφείο A2G και ποια είναι η φιλοσοφία πίσω από το σχεδιασμό σας; Το γραφείο «A2Γ Αρχιτέκτονες» ιδρύθηκε…

Η ΛΊΝΑ ΓΚΟΤΜΈ ΕΠΑΝΑΣΧΕΔΙΆΖΕΙ ΤΟΝ ΚΌΣΜΟ ΜΕ ΑΡΧΈΣ ΤΗΝ ΟΙΚΟΛΟΓΊΑ, ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΊΑ ΚΑΙ ΤΟΝ ΆΝΘΡΩΠΟ

Για τη Lina Ghotmeh, η αρχιτεκτονική δεν είναι απλώς αντανάκλαση της κοινωνίας, αλλά μια ενεργή δύναμη που μπορεί να την επαναπροσδιορίσει. Μέσα από το έργο της, οι χώροι αποκτούν δημόσιο χαρακτήρα, προάγουν τη σύνδεση, την ενσώματη εμπειρία και τον σεβασμό προς το περιβάλλον. Πιστεύει βαθιά ότι η σχέση ανθρώπου και χώρου είναι διαλεκτική: η αρχιτεκτονική επηρεάζει, αλλά και επηρεάζεται από τον τρόπο ζωής και τις κοινωνικές αλλαγές.

LINA GHOTMEH’S ARCHITECTURE RESPECT FOR NATURE AND CARE FOR PEOPLE

For Lina Ghotmeh, architecture is not merely a reflection of society—it is an active force capable of redefining it. Through her work, spaces take on a public character, fostering connection, embodied experience, and respect for the environment. She deeply believes that the relationship between people and architecture is dialectical: architecture shapes the way we live, even as it is shaped by social change.

Osaka, Japan

Anatomy of a Dhow, Bahrain Pavilion

Osaka Expo2025 © Lina Ghotmeh — Architecture

Photo © Ishaq Madan

2023-2025

Η αρχιτεκτονική σας γλώσσα συνδυάζει την ποίηση, τη μνήμη και την υλικότητα. Πώς ξεκινά ένα αρχιτεκτονικό σας ταξίδι;

Η αρχιτεκτονική μας προσέγγιση ξεκινά πάντα από την έρευνα. Πριν από οτιδήποτε άλλο, εμβαθύνουμε στην ιστορία του τόπου, αναζητούμε πώς το έργο μπορεί να είναι πραγματικά ριζωμένο στο περιβάλλον του. Υπάρχει έντονη η έννοια της «αρχαιολογίας», όχι όμως με την παραδοσιακή σημασία, αλλά ως μια διαδικασία που μας οδηγεί προς το μέλλον. Κάθε νέο έργο ξεκινά με μια ερώτηση, όχι με μια έτοιμη απάντηση. Αυτή η ερώτηση μάς συνοδεύει καθ’ όλη τη διάρκεια της διαδικασίας, εξελίσσεται, εμπλουτίζεται και τελικά διαμορφώνει το αποτέλεσμα. Όταν μιλάμε για μια «αρχαιολογία του μέλλοντος», εννοούμε μια περιβαλλοντική έρευνα με βάθος και πολυπλοκότητα. Μελετάμε το περιβάλλον με την ευρύτερη έννοια, υλική, άυλη ή και κοινωνική, και ενσωματώνουμε αυτές τις διαφορετικές «στρώσεις» μέσα στην ίδια την αρχιτεκτονική.

Your architectural language blends poetry, memory, and materiality. How do you begin a design journey?

Well, our process is based on research. We always start by looking into the history of a place—exploring how the project is truly anchored in its environment. There’s a notion of archaeology that’s very much present, but not archaeology in the traditional sense. It’s an archaeology that leads us toward the future. So every new project begins with a question, rather than a fixed answer. That question becomes part of the process—it stays with us, evolves, and enriches the final outcome. When we speak of an “archaeology of the future,” it takes the form of an environmental research that’s both intrinsic and layered. We study the environment in a broad sense—whether it’s physical, immaterial, or social—and we blend those layers into the architecture itself.

London, United Kingdom

Serpentine Pavilion 2023 designed by Lina Ghotmeh. © Lina Ghotmeh — Architecture

Photo: Iwan Baan, Courtesy: Serpentine.

2022-2023

Σε μια εποχή όπου η βιωσιμότητα δεν είναι πλέον επιλογή αλλά αναγκαιότητα, πώς επαναπροσδιορίζετε την οικολογική ευθύνη μέσα από την αρχιτεκτονική;

Η βιωσιμότητα είναι βασικό στοιχείο της δουλειάς μας, αλλά για μας δεν αφορά μόνο την οικολογία. Στόχος μας είναι η αρχιτεκτονική να έχει θετικό αντίκτυπο στο περιβάλλον, στη φύση και στις κοινότητες. Θέλουμε να δημιουργούμε χώρους όμορφους, με ταυτότητα και μνήμη, χώρους που αγαπιούνται και προσφέρουν χαρά στους ανθρώπους. Αυτή η αίσθηση της μαγείας, της σύνδεσης με κάτι μεγαλύτερο, είναι μέρος της οικολογικής ευθύνης. Όταν η αρχιτεκτονική σέβεται τον τόπο και λειτουργεί σε αρμονία με τη φύση, τότε φροντίζει πραγματικά τη γη, τους ανθρώπους και το μέλλον.

In an age where sustainability is no longer optional but essential, how do you redefine ecological responsibility through architecture?

Sustainability is very present in our work—it’s fundamental. But for us, it’s not only about ecology. It’s about creating architecture that has a positive impact, whether that’s on the environment, on nature, or on the communities that inhabit it. It’s also about creating a sense of beauty, a sense of belonging, and a sense of memory in each project. In the end, it’s designing spaces that are loved—spaces where people feel happy to live. That’s where this idea of enchantment comes in. Enchantment prolongs the beauty of the world. It reveals the beautiful parts of the world that are often obscured by everyday routines, or by larger events we live through. So that’s what we try to do with architecture—to bring forth that sense of enchantment. When architecture is drawn in synergy with its environment and with nature, when there is respect embedded in its form, then there is ecological responsibility as well. It’s about care—care for the land, for the people, and for the future.

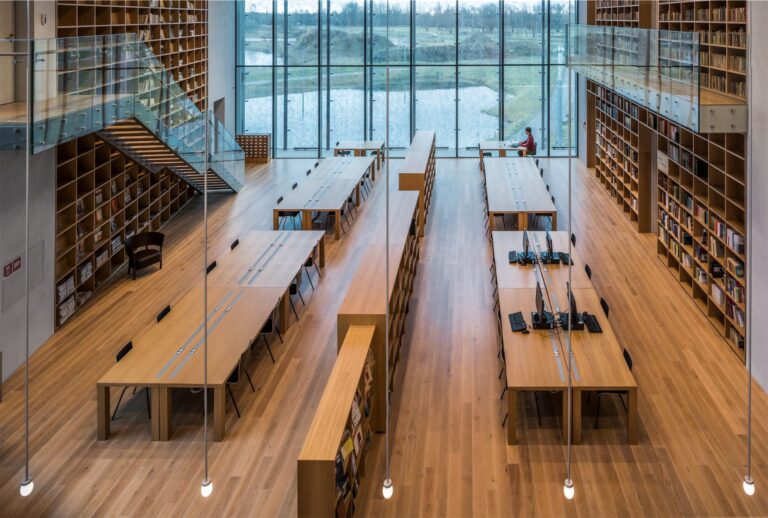

Tartu, Estonia

Ethnographic Museum

Photo © Takuji Shimmura

Lina Ghotmeh with Dorell.Ghotmeh.Tane

2006-2016

Πιστεύετε ότι οι δομημένοι χώροι διαμορφώνουν τον τρόπο που ζούμε και σχετιζόμαστε, ή η αρχιτεκτονική ακολουθεί πάντα τις κοινωνικές αλλαγές;

Πρόκειται για μια διαλεκτική σχέση που λειτουργεί και προς τις δύο κατευθύνσεις. Η αρχιτεκτονική επηρεάζει βαθιά τον τρόπο που ζούμε και σχετιζόμαστε και το έχουμε δει αυτό μέσα από τα έργα μας. Στον χώρο του εστιατορίου στο Palais de Tokyo στο Παρίσι, για παράδειγμα, οι άνθρωποι άγγιζαν τα υλικά, συνδέονταν σωματικά και συναισθηματικά με τον χώρο. Τα φυσικά υλικά, χώμα και ξύλο, δημιούργησαν μια αίσθηση σεβασμού και συμμετοχής. Στα εργαστήρια της Hermès, οι τεχνίτες μάς είπαν πως ένιωθαν στη δουλειά σαν να ήταν σε διακοπές. Αυτό δείχνει πως οι χώροι εργασίας δεν χρειάζεται να είναι αυστηροί ή ψυχροί. Μπορούν να είναι πηγές χαράς και έμπνευσης. Το Εθνικό Μουσείο της Εσθονίας σχεδιάστηκε με επίκεντρο τον δημόσιο χώρο. Η ίδια η στέγη γίνεται τόπος συνάντησης και κοινής εμπειρίας, φέρνοντας την κλίμακα του μεγάλου στο ανθρώπινο επίπεδο. Η αρχιτεκτονική μπορεί να αλλάξει τον τρόπο που σχετιζόμαστε με τον χώρο, με τη φύση και με τους άλλους. Είναι κοινωνική, ανθρώπινη και βαθιά συνδεδεμένη με τη ζωή. Η οικολογική της ευθύνη είναι επίσης αναπόσπαστο μέρος αυτής της προσέγγισης.

Do you believe built spaces shape how we live and relate—or is architecture always playing catch-up with social change?

It’s a dialectical relationship. It always works in two directions. Of course, architecture affects the way we live and relate to one another, and we believe in that very deeply. I’ve seen it in the way the spaces we’ve designed have created new forms of engagement. Take the restaurant at the Palais de Tokyo, part of the Contemporary Art Museum in Paris, for instance—when it opened, people came in and started touching the furniture, the materials, they engaged with the space. The project was built entirely with natural materials—earth, wood—and people connected with that. There was this sense of respect, of tactile engagement with the environment around them. Or consider the Hermès Workshops: the artisans working there told us they felt like they were going on vacation when they came to work. And that’s significant. Workplaces don’t need to feel harsh or disciplinary—they can be places of pleasure, of beauty, of inspiration. That changes the way we relate not only to work but to each other. It creates a different rhythm, a different sense of being. In every project we create, there’s a public aspect—a sense of choreography that opens the space to others. At the Estonian National Museum, the whole design was imagined around the importance of public spaces. The roof becomes a place where people gather, appropriate their history, and enter under a large cantilever that brings the community down to the human, individual scale. That’s social architecture—thinking at the scale of the human being, but also at the scale of the living more broadly. Ecological impact is part of that too.

Υπήρξε κάποιο έργο που άλλαξε βαθιά την οπτική σας, επαγγελματικά ή προσωπικά;

Ναι, το Stone Garden, το κτήριο που ολοκληρώσαμε στη Βηρυτό. Ήταν ένα έργο που είχε βαθιά προσωπική απήχηση, καθώς βρίσκεται στην πατρίδα μου. Μέσα από τη διαδικασία του σχεδιασμού, προσπαθούσα επίσης, ίσως ασυνείδητα, να βρω αρχιτεκτονικές απαντήσεις στα ερωτήματα που θέτει η ίδια η Βηρυτός: Πώς ζούμε σε μια πόλη που έχει σημαδευτεί από πόλεμο και καταστροφή; Πώς σχεδιάζουμε σπίτια που σέβονται το κλίμα αντί για γυάλινους πύργους; Πώς επανεισάγουμε τη φύση στην πόλη; Το έργο συνέδεσε προσωπικές και συλλογικές μνήμες, τον πόνο, την ομορφιά και την ανθεκτικότητα της Βηρυτού, και τα εξέφρασε μέσα από τη μορφή. Επίσης, αποτέλεσε σημείο-κλειδί για την έρευνα υλικών στην πρακτική μου, καθώς οι πειραματισμοί στην πρόσοψη επηρέασαν πολλά μελλοντικά μου έργα.

Was there a particular project that profoundly transformed your outlook—either as a professional or on a personal level?

Yes—Stone Garden, the building we completed in Beirut. It was a project that had a deep personal resonance. It was very emotional from the beginning—it’s in my hometown. It became a way for me to question my own memories, my own upbringing. Through the design process, I was also trying—maybe unconsciously—to find architectural answers to the questions that Beirut itself raises: How do we live in a city marked by war and destruction? How do we design homes that respond to climate rather than rely on glass towers? How do we create buildings that reintroduce nature into the city? So, it brought together many personal and collective memories—the trauma of the city, beauty, resilience—and allowed them to be expressed through form. It was also a turning point for my material research in the practice. The experiments we carried on that façade became central to many of my future projects.

Beirut, Lebanon

Housing and Mina Art Foundation

© Lina Ghotmeh — Architecture | Photo © Iwan Baan

2011-2020

Το όνομα «Stone Garden» φέρνει στο μυαλό κάτι αρχαίο και ζωντανό. Τι σημαίνει για σας σε προσωπικό και εννοιολογικό επίπεδο;

Κάθε έργο έχει για μένα το δικό του πνεύμα και προσωπικότητα, σαν να είναι ένας ζωντανός οργανισμός. Πιστεύω ότι η αρχιτεκτονική δεν είναι απλώς ένα στατικό αντικείμενο, αλλά κάτι που ανταποκρίνεται, προκαλεί συναισθήματα και συνδέεται με τους ανθρώπους. Η λέξη «Garden» αναφέρεται στη ζωή, στα φυτά που αναπτύσσονται μέσα στο κτήριο και φέρνουν τη φύση κοντά στους κατοίκους, συμβολίζοντας και την ελπίδα που αναγεννιέται ακόμα και μέσα από τα χαλάσματα, όπως στη Βηρυτό. Η «Stone» συμβολίζει την αντοχή και τη γλυπτική διάσταση του κτηρίου. Το κτήριο είναι σμιλευμένο από τους περιορισμούς της πόλης, το κλίμα και τη μνήμη του τόπου. Η μορφή του θυμίζει τη φυσική ομορφιά των Παγόδων, τους βραχώδεις σχηματισμούς στην παραλία της Βηρυτού, που στέκουν αθόρυβοι μάρτυρες του χρόνου.

The name “Stone Garden” evokes something both ancient and alive. What does it signify to you on a personal and conceptual level?

I’ve come to understand that every project has, for me, its own spirit and its own personality. It’s almost as if it’s a living being. I’ve always resisted the idea that architecture is just an object, something static placed in a setting. For me, a building is an emergence—a being that responds, that evokes, that communicates. It holds stories and memories and has the potential to connect with people. Stone Garden draws its name from that dual nature. The “garden” refers to the presence of life—actual vegetation growing in the building, framing every loggia, every opening, bringing nature into direct contact with the residents. It’s also about hope—nature as something that can reemerge from the ruins, as it often does in Beirut, bringing beauty back into a wounded city. The “stone” speaks to permanence, to sculpture. The entire building is sculpted. It’s not just designed; it’s carved and shaped by the constraints of the urban regulations, the site, the climate, and the memory of the place. Its form echoes both the organic qualities of the site and perhaps also a reference to the Pigeon Rocks in the Mediterranean—those natural stone formations along Beirut’s Corniche that stand as quiet witnesses to time. The building, in a way, mirrors that kind of presence: something shaped by history, yet enduring.

Beirut, Lebanon

Housing and Mina Art Foundation

© Lina Ghotmeh — Architecture | Photo © Laurian Ghinițoiu

2011-2020

Το κτήριο φαίνεται να «αναπνέει» μέσα στην πόλη. Πώς καταφέρατε αυτή την αίσθηση φυσικής ένταξης στο αστικό

τοπίο;

Μου αρέσει πολύ αυτή η περιγραφή, «αναπνέει». Σκέφτομαι τα κτήριά μας σαν ζωντανούς οργανισμούς, όχι ως απλά αντικείμενα. Το κτήριο συνδέεται με το περιβάλλον του μέσα από αυτή την ανάσα: με τη φύση που περικλείει, τη ζωή των κατοίκων, τα πουλιά που πετούν μέσα από τις λότζιες και την ενέργεια που αναπτύσσεται μέσα στους τοίχους του. Υπάρχει μια συνεχής κίνηση, όχι μόνο φυσική αλλά και βιωματική. Κάθε διαμέρισμα είναι διαφορετικό, με μοναδικά χαρακτηριστικά. Το ένα έχει μεγάλα παράθυρα που ανοίγουν σε θέα, το άλλο πιο μικρά, πιο οικεία ανοίγματα. Υπάρχει ρυθμός και ροή, τόσο κάθετα όσο και οριζόντια. Ακόμα και οι χώροι κυκλοφορίας ζωντανεύουν. Η είσοδος επεκτείνεται προς τα έξω, δημιουργώντας έναν μεταβατικό χώρο ανάμεσα στο δημόσιο και το ιδιωτικό. Η κίνηση αυτή, η εναλλαγή ανάμεσα στο φανερό και το κρυφό, δίνει την αίσθηση της αναπνοής. Το κτήριο αναπνέει τη μνήμη της πόλης, προσφέροντας ταυτόχρονα μια ζωντανή, δυναμική παρουσία.

The building seems to “breathe” within the city. How did you achieve this sense of natural integration into the urban landscape?

That’s such a lovely way to describe it—“breathing.” I often think of our buildings as animate beings, not objects. So, this idea of breathing is exactly right. The building connects to its surroundings through that—it breathes. It breathes through the nature it contains, through the lives of its residents, through the birds that now fly through the loggias, and through the life that has developed within its walls. There’s constant movement—not just physical, but experiential. Every apartment is different from the next. The spaces are not repetitive; each one unfolds in a unique way. One level opens with a large, framed window, offering a view of nature and the city beyond. Another might have a smaller opening, more intimate, more internal. There’s a rhythm to it—a flow that continues both vertically and horizontally. Even the circulation is alive. The lobby extends into the outside, becoming an in-between space that transitions from public to private. It’s always about revealing and concealing, framing and flowing. This movement and variation create that sensation of breath. The building breathes the memory of the city, but it also offers a dynamic present—an architecture that is constantly alive.

Η Μεσόγειος είναι ένας τόπος με μνήμη και μυθολογία. Θα σας ενδιέφερε η ιδέα να σχεδιάσετε στην Ελλάδα ή σε κάποιο από τα ελληνικά νησιά;

Ταξιδεύω αρκετά στα ελληνικά νησιά και νιώθω ότι συνδέομαι με αυτά. Θα έλεγα ότι η Μεσόγειος συνδυάζει διαφορετικές αντανακλάσεις του ίδιου νομίσματος. Φαντάσου ένα αντικείμενο που λαμπυρίζει στο φως· παραμένει βέβαια το ίδιο, αλλά κάθε φορά αντανακλά το φως διαφορετικά. Αυτό συμβαίνει επίσης επειδή είναι έντονα καθορισμένη από τη γεωγραφία της. Πιστεύω ότι ως άνθρωποι ταυτιζόμαστε περισσότερο με τις τοποθεσίες, τις ρίζες μας, παρά με τα εθνικά μας σύνορα. Συνδεόμαστε με τα μέρη που μας διαμόρφωσαν: μέσα από το κλίμα, τις γεύσεις, τις σχέσεις που είχαμε εκεί με τους ανθρώπους, με την τοπογραφία, με το περιβάλλον. Και το ελληνικό πλαίσιο είναι ένα τοπίο με το οποίο αισθάνομαι οικεία.

The Mediterranean is a landscape with memory and myth. Would you be in trigued by the idea of designing in Greece—or elsewhere in the Greek islands?

I spend a lot of time traveling around the Greek islands, and I do identify with the region. The Mediterranean region is one that I would say is like various shimmers of the same coin. You can imagine one object glimmering in the light—it’s still one object, but it shimmers differently each time. That’s also because it is very much marked by its geography. I do believe that we, as humans, identify with our geographies—our roots—rather than our national boundaries. We relate to the places that constitute us: in terms of climate, in terms of what we’ve eaten there, or how we’ve related to others there—to the geography, to topography. And the Greek context is one that I feel very attached to.

Normandy, France

Πιστεύετε ότι υπάρχει ένα «γυναικείο βλέμμα» στην αρχιτεκτονική; Και αν ναι, πώς το εκφράζετε στο έργο σας, ως γυναίκα που δρα και επαναπροσδιορίζει έναν παραδοσιακά ανδροκρατούμενο χώρο;

Είναι αδιαμφισβήτητο ότι το δομημένο περιβάλλον μας έχει διαμορφωθεί μέσα από το πρίσμα μιας πατριαρχικής κοινωνίας, που συχνά αποκλείει τη διαφορετικότητα. Οι πόλεις μας πολλές φορές δεν αντανακλούν ποιοι πραγματικά είμαστε, γυναίκες, διαφορετικά φύλα, φυλές ή καταγωγές.Δεν είμαι σίγουρη αν θα το χαρακτήριζα «γυναικείο βλέμμα», αλλά μάλλον μια ευαισθησία που πηγάζει από τη διαφορετικότητα. Υπάρχει μια ηγεμονική προσέγγιση στον τρόπο που χτίζουμε, ο οποίος απομακρύνεται από τη φύση και προκαλεί αποκλεισμούς. Οι πόλεις μπορεί να αποπνέουν βία, όχι μόνο μέσω της εγκληματικότητας αλλά και μέσω του σχεδιασμού τους, αποκλείοντας ανθρώπους όπως γυναίκες, παιδιά και ηλικιωμένους. Στο έργο μου, θέλω να δημιουργώ χώρους πιο ανοιχτούς, διαπερατούς και συμπεριληπτικούς, που να σέβονται τη φύση και την ανθρώπινη πολυμορφία. Αυτή είναι η προσέγγισή μου για να επαναπροσδιορίσω έναν χώρο που παραδοσιακά κυριαρχείται από άνδρες.

As a woman navigating and reshaping a traditionally male-dominated field, do you feel that a “female gaze” exists in architecture? And if so, how does it manifest in your work?

I think it’s undeniable that our built environments have been produced through the lens of a patriarchal, male-dominated society. I often feel that our cities don’t reflect the diversity of who we are—as women, as different genders, colors, or origins. There’s a kind of hegemony in the way we build—one that often disconnects from nature, that imposes aesthetic codes and standards that attempt to build boundaries. And that feeling makes me want to contribute differently—to express space through another sensitivity. I’m not sure I would call it a “female gaze,” but rather a gaze rooted in diversity. Cities can sometimes feel violent. And that’s not just about crime—it’s about how they’re built, who they were built for, and who was excluded. They often overlook children, the elderly, women, the living world—beings who move through space differently. So, for me, it’s about making space more porous, more inclusive.

Ο επανασχεδιασμός της Δυτικής Πτέρυγας του Βρετανικού Μουσείου είναι ένα εγχείρημα μεγάλης κλίμακας. Πώς προσεγγίζετε συναισθηματικά και πνευματικά έναν χώρο τόσο φορτισμένο ιστορικά;

Πιστεύω πως κάθε έργο που αναλαμβάνουμε φέρει ένα ιστορικό βάρος. Είναι κάτι που έχουμε μάθει όχι μόνο να αποδεχόμαστε αλλά και να αναζητούμε. Μεγαλώνοντας στη Βηρυτό, ανάμεσα σε πληθώρα πολιτισμών και αφηγήσεων, η ιστορία δεν είναι κάτι αφηρημένο, είναι μέρος της καθημερινότητας. Ζεις μέσα σε ερείπια, μνήμες, αντιφάσεις. Κι αυτό διαμορφώνει την οπτική σου για τον κόσμο. Όταν προσεγγίζουμε έναν τόπο, είτε πρόκειται για ένα σοβιετικό αεροδρόμιο στην Εσθονία είτε για το κατακερματισμένο τοπίο της Βηρυτού, ήδη συνομιλούμε με πολλαπλές χρονικές διαστάσεις. Στην περίπτωση του Βρετανικού Μουσείου αυτό είναι ακόμα πιο έντονο. Το βάρος του παρελθόντος δεν είναι μόνο υλικό, αλλά και εννοιολογικό, ενσωματωμένο στις συλλογές, τις αφηγήσεις, τις αντιπαραθέσεις. Για παράδειγμα, κάτω από τα Εργαστήρια Hermès ανακαλύψαμε ένα στρώμα της Μαγδαληναίας εποχής, μιας προϊστορικής χρονικής περιόδου. Και ξαφνικά βρίσκεσαι σε ένα άλλο χρονικό σημείο. Το ερώτημα είναι πώς μπορεί η αρχιτεκτονική να διαχειριστεί όλα αυτά τα επίπεδα χωρίς να τα ισοπεδώσει. Για μας, το Βρετανικό Μουσείο είναι ο απόλυτος χώρος διαλόγου, ένας τόπος όπου τα αντικείμενα μιλούν και οι ιστορίες τέμνονται. Ο ρόλος μας ως αρχιτέκτονες δεν είναι να κυριαρχήσουμε στον χώρο, αλλά να τον διαμορφώσουμε έτσι ώστε να ενθαρρύνει τον διάλογο, τη συμμετοχή και να επιτρέπει την πολυπλοκότητα.

Redesigning the Western Wing of the British Museum is no small undertaking. How do you emotionally and intellectually enter a space so loaded with historical weight?

I think every project we take on carries a certain historical weight. It’s something we’ve come to embrace—maybe even seek. Growing up in Beirut, surrounded by overlapping layers of civilizations and stories, history isn’t something abstract. It’s part of your everyday environment. You live among ruins, memories, contradictions. That shapes how you see the world. So when we approach a site—whether it’s the Soviet-era airfield in Estonia, or the fractured landscape of Beirut—we’re already in conversation with multiple temporalities. In the case of the British Museum, it’s perhaps even more intense. The weight of the past is not only physical but also conceptual—held in the collections, the controversies, the narratives. We discovered, for example, a Magdalénien layer beneath the Hermès Workshops—a prehistoric level of history—and suddenly, you’re with ancient time. It becomes about understanding how architecture can navigate all these layers without flattening them. For us, the British Museum is the ultimate space for dialogue—a place where objects speak, where stories intersect. And as architects, our role is to become facilitators. Not to dominate the space, but to help shape it in a way that fosters conversation, that invites participation, and that allows for complexity to be held, not erased.

Καθώς η Ελλάδα ανανεώνει το αίτημά της για επανένωση, μπορεί η αρχιτεκτονική να αποτελέσει ένα ήσυχο αλλά ισχυρό εργαλείο σε τέτοιους πολιτιστικούς διαλόγους;

Όταν συμμετείχαμε στον διαγωνισμό με τη δική μας πρόταση, μας δόθηκε για μελέτη το Μαυσωλείο της Αλικαρνασσού. Αναρωτιόμασταν πώς ο χώρος θα μπορούσε να λειτουργήσει ως τόπος διαλόγου, όχι ως μία κλασική αίθουσα εκθέσεων, αλλά ως χώρος όπου μπορούν να αναδυθούν πολλαπλές οπτικές. Αντί να παρουσιάζουμε τα αντικείμενα με τον παραδοσιακό τρόπο, θέλαμε να τους δώσουμε αξιοπρέπεια ως αυτόνομα έργα, επιτρέποντας στους επισκέπτες να συνδεθούν μαζί τους πιο άμεσα και ανοιχτά. Ο χώρος έπρεπε να ενθαρρύνει τη συζήτηση, όχι μόνο για να βοηθήσει τους επισκέπτες να κατανοήσουν πλήρως την ιστορική αξία των αντικειμένων αλλά και για να τους κάνει να σκεφτούν τις σύγχρονες προκλήσεις που αντιμετωπίζουν οι τόποι από όπου προέρχονται αυτά τα αντικείμενα. Στον σχεδιασμό μας, το ισόγειο λειτουργεί σαν μια ανοιχτή σκηνή, μια «ανοιχτή αρχαιολογία» που παραπέμπει στον σημερινό χώρο του Μαυσωλείου στη Μπόντρουμ. Είναι σχεδιασμένο ώστε να προσκαλεί σε πολυεπίπεδη ερμηνεία και διάλογο. Η αρχιτεκτονική εδώ γίνεται μέσο συνύπαρξης πολλαπλών οπτικών. Γύρω από τον κεντρικό χώρο του ισογείου τοποθετήσαμε και εκπαιδευτικές ζώνες, αφιερωμένες στη συζήτηση και την ανταλλαγή απόψεων. Με αυτόν τον τρόπο, το ίδιο το κτήριο ενθαρρύνει τη συζήτηση γύρω από την προέλευση και τη συνεχιζόμενη σημασία των εκθεμάτων. Πιστεύουμε πως ο χώρος έχει δύναμη, μπορεί να γεννήσει διάλογο και συνείδηση.

As Greece renews its call for reunification, can architecture become a quiet but powerful tool in such cultural conversations?

When we responded to the competition with our design, we were given the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus as a case study. We began by imagining how the space could become a site for dialogue—not a traditional exhibition space, but one where multiple perspectives could emerge. Rather than displaying artifacts in a classical manner, we wanted to give them dignity as freestanding objects, allowing visitors to engage with them more openly. The space needed to foster conversation—not only to help visitors fully understand the historical value of the artifacts, but also to reflect on the contemporary challenges faced by the places these objects come from. In our design, the ground floor functions like an open stage—an “open archaeology” that evokes the current site of the Mausoleum in Bodrum. It’s conceived as a space that, like the archaeological site itself, invites layered interpretation and dialogue. Architecture here becomes a medium through which multiple perspectives can coexist. Additionally, surrounding the central space on the ground floor, we envisioned educational areas dedicated to debate and exchange. In this way, the design encourages conversations around both the origins and the continued relevance of these objects. We believe that space itself can play a powerful role in fostering dialogue.

050623_0424

050623_0424

Serpentine 23 LGA 0774

Serpentine 23 LGA 0774

Serpentine 23 LGA 0943

Serpentine 23 LGA 0943

Serpentine 23 LGA 1060

Serpentine 23 LGA 1060

Serpentine 23 LGA 1416

Serpentine 23 LGA 1416

BH PAV -2

BH PAV -2

BH PAV -28

BH PAV -28

BH PAV -48

BH PAV -48

BH PAV -55

BH PAV -55

BH PAV -62

BH PAV -62

BH PAV -106

BH PAV -106

BH PAV -115

BH PAV -115

BH PAV -143

BH PAV -143

2Z9A1931_DxO

2Z9A1931_DxO

2Z9A1962_DxO

2Z9A1962_DxO

2Z9A2169_DxO

2Z9A2169_DxO

2Z9A9561

2Z9A9561

x js-estonia-nm-0875

x js-estonia-nm-0875

Model submitted by Lina Ghotmeh Architecture for competition

Model submitted by Lina Ghotmeh Architecture for competition

2 Laurian G

2 Laurian G

copyright_laurianghinitoiu_stonegarden_linagotmeh (9 of 28)

copyright_laurianghinitoiu_stonegarden_linagotmeh (9 of 28)

Stone Garden 2

Stone Garden 2

Stone Garden LGA 5551

Stone Garden LGA 5551

Stone Garden LGA 5580

Stone Garden LGA 5580

Stone Garden LGA 5940

Stone Garden LGA 5940

Stone Garden LGA Iwan-Baan_01

Stone Garden LGA Iwan-Baan_01

Stone Garden LGA Iwan-Baan_02

Stone Garden LGA Iwan-Baan_02